A Cognitive Behavioral Systems Approach to Family Therapy

12. The cognitive behavioural frame of reference

Overview

Cerebral behavioural therapy (CBT) is a popular and testify-based psychotherapeutic approach. Whilst its guiding principles are associated with aboriginal Greek thought, current developments emanate from the modern theoretical frameworks of behavioural therapy and cerebral therapy. Gimmicky CBT represents a wide church of theoretical developments, interventions and professional groupings (British Association for Behavioural and Cerebral Psychotherapies 2003).

This affiliate outlines the development and general principles of CBT. It continues by examining CBT'south theoretical framework and general characteristics. Having provided an overview of CBT in full general, the chapter explores the diverse uses of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference in occupational therapy. In doing so, the criticisms that have been fabricated of occupational therapists' utilise of CBT to appointment are best-selling and proposals for ways in which the strengths of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference can be integrated within occupationally focused exercise are offered.

Introduction

CBT'southward robust and developing evidence base of operations has consistently drawn occupational therapists to use it in practice. However, in doing so, the potential to become a full general mental wellness practitioner and not an occupational therapist has been noted. Considerable debate has taken place regarding the fact that occupational therapists may bear out CBT as a form of psychotherapy. The case for occupational therapists' use of their shared skills in this respect has been given elsewhere (Duncan, 1999, Duncan, 2003a, Duncan, 2003b, Harrison, 2003 and Stewart, 2003) and will non exist repeated hither. Distancing from the occupational therapy function is, notwithstanding, not essential in order for a clinician to use a CBT arroyo in practice. In fact, the incorporation of a cerebral behavioural frame of reference within occupational therapy is non merely achievable simply too highly desirable. Therefore, this affiliate focuses on the utilize of a cognitive behavioural frame of reference within an occupational therapy context.

What is CBT?

Historical evolution

CBT is a dynamic trunk of knowledge that has developed since the 1950s. It is strongly influenced by the theoretical and therapeutic traditions of behavioural therapy and cognitive therapy. Behavioural therapy, in turn, has been significantly shaped by the evolutionary perspective of health. Its developmental roots stretch back to the kickoff of the 20th century, when animate being behaviour research was carried out and related to human being beings (Hawton et al 1996). Cognitive therapy, whilst developing after than behavioural therapy, claims more historic roots. It cites the Roman emperor Epictetus, who wrote, 'Men are disturbed, not by things, just of the view they take of them', as an example of the early on recognition of the ability of idea on health (Beck et al 1979).

Behavioural therapy

Ii principles of animate being learning theory accept affected the evolution of behavioural therapy: classical conditioning and operant conditioning (Bernstein 1996). Both classical and operant workout are briefly outlined below; however, readers are encouraged to refer to other texts for a more comprehensive overview of these important theories.

Classical conditioning

Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist, developed the theory of classical conditioning at the turn of the 20th century. Nevertheless, the original development of this theory could not have been further from its eventual applied function within behaviour therapy. Classical conditioning was discovered during an experiment into the digestive procedure of dogs, a report that would win Pavlov the Nobel Prize for Physiology/Medicine in 1904. In 1913, John Watson employed classical conditioning theory in the evolution of behaviourist theory. Watson's theory was popular, every bit it offered an objective and measurable basis for human behaviour, an approach that was in stark contrast to the other predominant psychological theories of the time (Hawton et al., 1996 and Duncan, 2003a).

Operant conditioning

The second influential learning theory in the evolution of behavioural theory was operant conditioning. This outlines 'the Law of Event', whereby a behaviour that is rewarded will tend to be repeated, and behaviour that is punished volition diminish (Hawton et al 1996).

Burrhus F. Skinner, an American psychologist, developed Pavlov's work by extending the principle of reinforcement. Previously, an action was considered to exist reinforced if it increased or decreased behaviour. Skinner explored different types of reinforcers and consequences. It was observed that different types of reinforcers had different furnishings on behaviour, depending upon the nature of the activity. Together, classical and operant conditioning provided the theoretical foundation for a variety of behaviour therapy interventions, mainly in mental wellness settings (Hawton et al 1996).

Whilst the benefits of behaviour therapy were widely recognized, the late 1960s and early on 1970s witnessed a developing disillusionment with behaviour therapy as the theoretical shortcomings and practical failures associated with the approach came into focus. Such disillusionment, at to the lowest degree amidst some, supported the nascence of another, related form of therapy known as cognitive therapy.

Cerebral therapy

The original attribution of a cerebral arroyo to therapy is given to Mechinbaum (1975). Even so, it is the work of Aaron T. Beck, an American psychiatrist, that has become synonymous with the term cerebral therapy.

'Aaron Beck (b. 1921) developed cerebral therapy though an examination of the links betwixt the environment, the person and his/her emotion and motivation. Surprisingly, Beck, a medical doctor, did not come up from a foundation in behaviorism. Instead, Beck'south theoretical roots were found in the psychoanalytical perspective' (Duncan 2003a). Beck's career commenced in psychiatry, and he trained in psychoanalytical theory and practice. Despite initially questioning the nature of psychoanalytical theory, he embraced the arroyo, even undertaking enquiry aimed at proving the efficacy of the approach in relation to low. Even so, this study reignited his initial doubts about psychoanalytical theory and in doing so led to the development of cerebral therapy. Later, Beck has published extensively on the theory and practice of cognitive therapy. For those who are interested in finding out more than about Aaron Brook, a biography of his life and work has been published (Weishaar 1993).

Cerebral therapy and behaviour therapy, whilst taking significantly different views about the causal factors of a disorder (i.e. that it has a cerebral or behavioural root), have many commonalities. It was perhaps inevitable, therefore, that both theories became combined into the mostly accepted framework of cognitive behavioural therapy.

Weather condition in which CBT is usually used

Owing to its strong evidence base in a variety of contexts (e.m. anxiety, low and psychosis) (Department of Health 2001) and support in a range of clinical guidelines from both the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (Dainty) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), CBT has go an increasingly popular method of intervention and has swiftly developed over the terminal xx years. Likewise equally having a strong show base for practice in the forenamed conditions, CBT is often associated with interventions to address alcohol abuse (e.g. Longabaugh & Morgenstern 1999), personality disorders (e.g. Young, 1999 and Davidson et al., 2006), family therapy (e.g. Epstein 2003) and drug corruption (e.g. Brook et al 1993, Waldron & Kaminer 2004). Likewise equally weather condition traditionally found within the mental health spectrum of interventions, CBT has also been positively associated with various other atmospheric condition, including chronic pain (Potent 1998, McCracken and Turk, 2002 and Vlaeyen and Morley, 2005) and chronic fatigue syndrome (Prins et al., 200l and Price et al., 2008).

An introduction to the theoretical framework of CBT

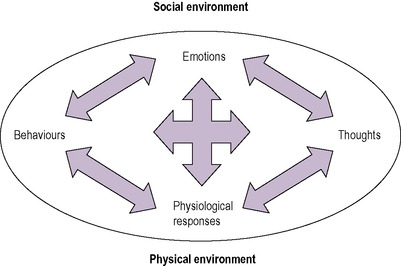

CBT takes a problem-focused perspective of life difficulties and focuses on five aspects of life experience:

• physiological responses

• the surround (Greenberger & Padesky 1995).

Each aspect of life experience is influenced by the social and physical surroundings in which they are placed (Fig. 12.ane). CBT suggests that changes in any gene tin can pb to an improvement or deterioration in the other factors. For case, if we practice (behaviour), we experience better (mood); if we experience nervous (mood), we may experience an increased centre charge per unit or sweat more (physiological reaction); if we discover large social gatherings difficult (social environs), nosotros may avoid them (behaviour).

| |

| Fig. 12.1 • The influence of the social and physical environment on aspects of life feel. (Reproduced with the permission of Kathlyn L. Reed.) |

The style in which CBT is delivered depends on the training of the therapist and the needs of the customer. In practice, the bulk of clinicians using these approaches draw from its richness of technique and theory. However, therapists' training and personal preferences can lead to a greater accent on a cognitive or behavioural approach:

• Cognitive therapy places an emphasis on rapid and automated interpretations of events and the importance of underlying beliefs and values.

• Behaviour therapy emphasizes our automatic learned responses to stimuli and the way in which our behaviour is shaped past its consequences.

One of the key theoretical components to understanding the theoretical basis of CBT is its postulated levels of cognition.

Levels of cognition

Cognitions are the way in which we know, sense or perceive reality (Chambers 1994) (Box 12.1). Beck et al (1979), in their seminal text, Cerebral Therapy of Depression, outlined three levels of cognition that are acquiescent to therapeutic intervention. Key to this conceptualization is the idea that, unlike other psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g. psychodynamic psychotherapy), each of these levels is accessible by the customer. The levels are hierarchical in nature, with automatic thoughts being the near frequently occurring and easily accessible, beliefs beingness more than abiding and core schema representing the building blocks of thought processes and being more challenging to shift.

Box 12.1

Action

Imagine y'all are comatose in bed … Of a sudden y'all are awakened past a loud crashing sound from downstairs. How would you experience?

• How would y'all feel if you lot knew there had been a spate of violent burglaries in your neighbourhood?

• How would yous feel if you had merely bought a new kitten that has been knocking over everything in sight?

The nature of feelings is largely determined past the way nosotros remember.

Automatic thoughts

Automatic thoughts are habitual and plausible. They are the uninvited thoughts that popular into your head (e.g. 'I'll sound stupid if I enquire a question in this grade'). Anybody has automated thoughts and it is likely that you will take some whilst reading this chapter (e.chiliad. What am I having for tea? Is this going to help me with my assignment? When am I seeing my next client?). All the same, for clients, more often than not automatic thoughts volition be negative in nature. Some other feature of automatic thoughts is that they can be state of affairs-specific — a client may be plagued by unhelpful automatic thoughts whilst in a stressful work state of affairs and find it difficult to cope, whilst appearing to office without difficulty when in the abode surroundings.

It is useful to understand the automated thoughts a client is having, equally these can have a straight impact on their presentation in sessions and their ability to carry out solar day-to-day life activities. Several techniques can exist used to elicit automatic thoughts.

• Direct questioning. What is (was) going through your mind just now?

• Inductive questioning. Utilize a series of open questions and reflexive statements to help a client recall an emotional state of affairs (eastward.g. What happened adjacent? What did you do?).

• Re-enacting/recreating a situation. Apply imagery, office play and in vivo experiments.

• Recording thoughts. Use thought diaries and and so on.

Where thoughts are recognized as being unhelpful, the therapist and clinician can work together to help the customer to change the nature of their thinking — in the noesis that this will help their behaviour. Importantly, changing thoughts is not the same as thinking more positively, which is unlikely in itself to lead to improved functioning (Greenberger & Padesky 1995). Challenging automated thoughts is virtually gaining a sense of perspective on a state of affairs, taking alternative perspectives and exploring new perspectives and solutions. Methods to challenge thoughts include:

• Looking at the evidence:

○ What do I know about this situation?

○ How well practise my thoughts fit the facts?

○ Practice I have experiences that propose my thoughts are not completely true?

○ Would my thoughts be accepted as right past other people?

• Looking at other possible interpretations:

○ Are there other interpretations that fit the facts just as well?

○ How might a friend think of this state of affairs?

○ How will I call up about this in 6 months or a year?

• Looking at the helpfulness of thinking this way:

○ If the facts are bleak, does my mode of thinking aid?

○ Is this blazon of thinking probable to make me feel worse?

○ Am I brooding over questions with no articulate-cut answers?

○ Am I behaving in ways that may make the situation worse?

Beliefs

These are conditional beliefs that we hold virtually ourselves. They may be unhelpful in nature (e.1000. 'I e'er brand a fool of myself when I come across my friends in the pub'). Whilst automatic thoughts are ofttimes easily accessible, beliefs tend to be slightly less obvious. They can sometimes be inferred from individuals' actions. If beliefs are to be put into words, then they oftentimes take the form of 'if … then …' sentences (east.g. If I cannot do my job to perfection, then anybody will think I am a failure') or of statements that contain 'should' (due east.k. I should exist the life and soul of a party) (Greenberger & Padesky 1995). Conditional beliefs lie beneath and shape the automatic thoughts that pop into our head; they can be viewed equally guiding principles that affect our daily life experiences. All lives are governed by beliefs to a certain extent and these in turn govern our behaviour. Some people, however, develop unhelpful beliefs about a range of bug and these tin often significantly bear upon the way in which they lead their lives.

Whilst unhelpful behavior can be varied in nature, in that location are several categories in which the most common beliefs can exist placed. It is frequently helpful to discuss these categories with clients to see if any of them resonate with their experience (Box 12.two).

Box 12.2

Typical forms of unhelpful beliefs

Overgeneralization

• Making sweeping judgements on the basis of single instances. 'Everything I practise goes incorrect.'

Selective abstraction

• Attending but to negative aspects of feel. 'Non 1 good thing happened today.'

Dichotomous reasoning

• Thinking in extremes, as well known as blackness and white thinking. 'If I can't get information technology right, at that place's no indicate in doing it at all.'

Personalization

• Taking responsibleness for things that have niggling or nothing to practise with oneself. 'I must have washed something to offend him.'

Arbitrary influence

• Jumping to conclusions without enough evidence. 'This course is rubbish' (when y'all have only simply started it!).

Only gilded members can proceed reading. Log In or Register to go along

Source: https://musculoskeletalkey.com/the-cognitive-behavioural-frame-of-reference/

Post a Comment for "A Cognitive Behavioral Systems Approach to Family Therapy"